In order to understand how Haiti became the Western Hemisphere’s poorest nation, it is helpful to know a little about its troubled history of national debt, prejudicial trade policies by other countries and foreign intervention into its affairs. Occupying part of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, Haiti is a land of great misery and poverty populated by people of amazing resilience and spirit.

In order to understand how Haiti became the Western Hemisphere’s poorest nation, it is helpful to know a little about its troubled history of national debt, prejudicial trade policies by other countries and foreign intervention into its affairs. Occupying part of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, Haiti is a land of great misery and poverty populated by people of amazing resilience and spirit.

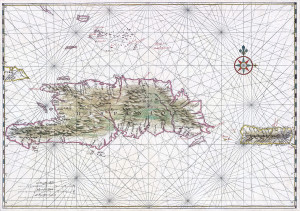

In his first trip to the New World in 1492, Columbus landed on the island that would become part of the expanding Spanish Empire. Spain eventually ceded the western one-third to France. By the end of the 18th century, the French colony had become the world’s foremost producer of coffee and sugar cane.

In his first trip to the New World in 1492, Columbus landed on the island that would become part of the expanding Spanish Empire. Spain eventually ceded the western one-third to France. By the end of the 18th century, the French colony had become the world’s foremost producer of coffee and sugar cane.

Essential to the colony’s productivity was a cruel and abusive slave system often regarded as the most brutal in the world. African slaves were worked hard by French plantation owners and their death rate was higher than anywhere else in the western hemisphere. Over a million perished during the colony’s hundred-year course and torture was routine; they were whipped, burned, buried alive, restrained and allowed to be bitten by swarms of insects, mutilated, raped and had limbs amputated.

Under these horrific conditions and with African slaves outnumbering white colonials by a ratio of ten-to-one, the stage was set for a slave insurrection led by Toussaint L’Ouverture in 1801. French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte attempted to suppress the burgeoning independence movement. In 1804, Jean-Jacques Dessalines and his followers eventually triumphed and Haiti became the world’s first independent black republic.

But the revolution had wrecked havoc on Haiti’s economy and the massacre of the minority white population shortly thereafter panicked colonial powers and slave-holding nations such as Britain and the US. Fearful of the influence of the slaves’ revolution, US President Thomas Jefferson refused to recognize the new republic, as did most European nations.

But the revolution had wrecked havoc on Haiti’s economy and the massacre of the minority white population shortly thereafter panicked colonial powers and slave-holding nations such as Britain and the US. Fearful of the influence of the slaves’ revolution, US President Thomas Jefferson refused to recognize the new republic, as did most European nations.

Since its inception, the country has experienced political and economic instability for most of its history. In 1825, King Charles X of France sent a fleet with the goal of reconquering the island. Then President of Haiti Jean-Pierre Boyer agreed to a treaty by which France formally recognized Haitian independence in exchange for a payment of 150 million francs, the modern equivalent of 17 billion dollars, saddling Haiti with interest and payments that crippled its economy.

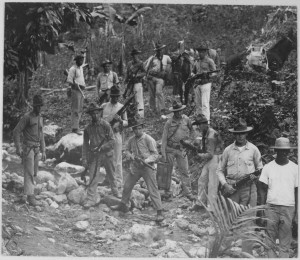

After a succession of dictatorships, a bankrupt Haiti accepted a US customs receivership from 1905 to 1941. In the interests of commercial control, US Marines occupied the country from 1915-1934. This action gave rise to growing anti-American sentiment and thousands of rebels were killed.

After a succession of dictatorships, a bankrupt Haiti accepted a US customs receivership from 1905 to 1941. In the interests of commercial control, US Marines occupied the country from 1915-1934. This action gave rise to growing anti-American sentiment and thousands of rebels were killed.

After US forces left in 1934, Dominican dictator Trujillo, one-quarter Haitian himself, used anti-Haitian sentiment as a nationalist tool and ordered his army to kill Haitians living on the Dominican side of the border. Political and economic tension between the two nations occupying the island of Hispaniola persists to-date.

In recent decades, Haiti’s history has been marked by economic hardship and political unrest. In the 1950’s, former voodoo physician Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier rose to power in a military coup and declared himself president for life. Duvalier maintained control over the population through a ruthless secret police known as the Tontons Macoutes. When he died in 1971, his 19-year-old son Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier took over and continued his father’s brutal reign. Popular discontent forced him out of power in 1986.

In 1990, an election was held and Roman Catholic priest Jean-Bertrand Aristide won the vote. Seven months into his term, Aristide was overthrown by a military coup and forced into exile. After three years of economic collapse and repression at the hands of the military regime, the United Nations intervened. In 1996, Aristide’s former prime minister, Rene Preval, was elected President.

For the next six years, Haiti witnessed relative economic growth. Aristide was elected president again in 2000 yet violence and human rights abuses became more prevalent. The unrest culminated in 2004 when celebrations marking the 200-year anniversary of the republic turned into a violent uprising against Aristide, forcing him into exile a second time. United Nations peacekeepers once again were sent in to stabilize the nation and Preval won his second presidency in 2006.

On January 12, 2010, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake rocked Haiti, leveling much of the capital of Port-au-Prince. The estimated death toll by the Haitian government is over 300,000. Five years later, many of the funds raised towards the country’s rebuilding have not reached those who needed it most.

On January 12, 2010, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake rocked Haiti, leveling much of the capital of Port-au-Prince. The estimated death toll by the Haitian government is over 300,000. Five years later, many of the funds raised towards the country’s rebuilding have not reached those who needed it most.